The circular economy: transformative vision or oxymoronic illusion?

The circular economy (CE) concept has gained unprecedented attention in the last 10 years. From the European Green Deal to the Chinese 5-year plan, and the corporate social responsibility strategies of firms like Renault, Ikea and Danone, the CE is now virtually everywhere. The CE is often promoted as a game-changing paradigm that can singlehandedly solve the manifold socio-ecological challenges of the 21st century. By narrowing, shortening and closing resource cycles, the CE is indeed expected to reduce environmental pollution, biodiversity loss, global warming, and resource depletion all while stimulating job creation and economic competitiveness. Yet, it is facing crucial challenges to deliver these promises.

“Civilisation is a hopeless race to discover remedies for the evils it produces”

The illusion of decoupling

First and foremost, CE proponents generally assume that economic growth can be decoupled from environmental exploration thanks to new technologies and socio-technical innovations that can decarbonise and dematerialise the economy (the so-called eco-economic decoupling). This assumption is deeply problematic because decades of scientific evidence have shown that the absolute decoupling of economic growth from environmental exploration is impossible (Albert, 2020; Haberl et al., 2020; Hickel and Kallis, 2019; Parrique et al., 2019; Ward et al., 2016).

While many believe that remanufacturing, refurbishing, recycling and other forms of material recovery can lead to perfect circular cycles, the reality is that materials degrade in both quality and quantity each time they are used or cycled, and each recovery process consumes significant amounts of energy (Bihouix, 2014; Monsaingeon, 2017). Moreover, recycling has many key limitations, and while some materials like metals can be recycled relatively easily, most others cannot. Recycled rubber, for example, has lower quality than virgin rubber and can thus only make a maximum of 5% of new rubber car tires (Campbell-Johnston et al., 2020). This is why, recycling and recovery can only cover a fraction of global material demand, meaning that the majority of global consumption still depends on natural resource extraction (Cullen, 2017; Haas et al., 2020).

A perfectly circular economy is therefore impossible to achieve in an industrial system and we should stop pretending this could be possible. Indeed, by suggesting that recycling is 100% effective and climate neutral, this discourse is discouraging the highest and most sustainable value-retention options: refuse and reduce. This discourse is also promoting the illusion that that hyper-consumption and hyper-materialism can carry on forever as long as consumers throw their waste in the right bin.

“A perfectly circular economy is therefore impossible to achieve in an industrial system and we should stop pretending this could be possible”

This framing is dangerous as it will most-likely increase humanity’s ecological footprint and prevent us from making important changes to create more sustainable lifestyles and consumption patterns, especially in the Global North. Research has indeed found that citizens in the high-income countries currently have an ecological footprint which is around 5 times higher than what is scientifically recognized as sustainable (Hickel, 2020a; Hickel and Kallis, 2019; Mont et al., 2014; Rijnhout et al., 2018). The scale of the reduction in ecological footprint needed for high-income countries to live within the biophysical limits of the Earth is so vast that scientists have recognised it is impossible to achieve while also growing GDP per capita (Albert, 2020; Haberl et al., 2020; Hickel and Kallis, 2019; Parrique et al., 2019).

This poses key systemic questions, as social scientists have long known that our current socio-economic system—capitalism—cannot operate without economic growth (Bookchin, 1971; Gorz, 1980; Hickel, 2020b; Latouche, 2009). A new circular society must thus be envisioned, one which does not depend on economic growth in order to function. A circular society which can operate within the biophysical boundaries of the Earth, while fairly and equitably distributing its limited resources.

“A new circular society must thus be envisioned, one which does not depend on economic growth in order to function”

The missing social dimension

This leads us to the second major limitation of the CE. As many scholars have rightly pointed out, the CE discourse, in its mainstream interpretations, currently lacks a social dimension (Calisto Friant et al., 2020; Clube and Tennant, 2020; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Hobson and Lynch, 2016; Klein et al., 2020; Lekan and Rogers, 2020; Lindgreen et al., 2020; Millar et al., 2019; Moreau et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2017). There is thus very little discussion on key aspects of the CE, such as who owns, controls and governs CE technologies and innovations, who pays for them and what implications this has for traditionally marginalized peoples. This depoliticized and uncontroversial discourse of the CE might have helped the concept rise-up the policy and business agendas, but it can lead to many negative consequences.

For instance, it can foster a circularity transition that replicates gender, ethnic, racial and class inequalities and that reinforces the power of dominant groups. It can lead to a circular future, where circular solutions are luxuries produced by a handful of dominant companies for a handful of wealthy people, in a handful of wealthy countries, while the rest of the world lives in imposed scarcity. A circular future must not only be ecologically sustainable, but it must also be democratically established and fair for all citizens on Earth. The Gilets Jaunes protests in France are a testimony of the dangers of a technocratic transition, which does not adequately address systemic issues of social equity and public participation.

“A circular future must not only be ecologically sustainable, but it must also be democratically established and fair for all citizens on Earth”

The transformative origins of the circular economy

Looking at the history of the CE concept, and the many discourses and visions that originated it, one can see that it builds on many ideas that actually address the two above-mentioned issues of decoupling and social justice and participation. In fact, the extensive research of Calisto Friant et al. (2020) and Clube and Tennant (2020), demonstrate that many earlier CE visions such as Buddhist economics, the blue economy, social ecology and regenerative design are significantly more socially transformative than mainstream CE propositions. As this interactive timeline of circularity thinking shows, by exploring over 70 related concepts from the Global North and South alike, the CE is not new nor alone, and many of its related concepts have addressed the above issues.

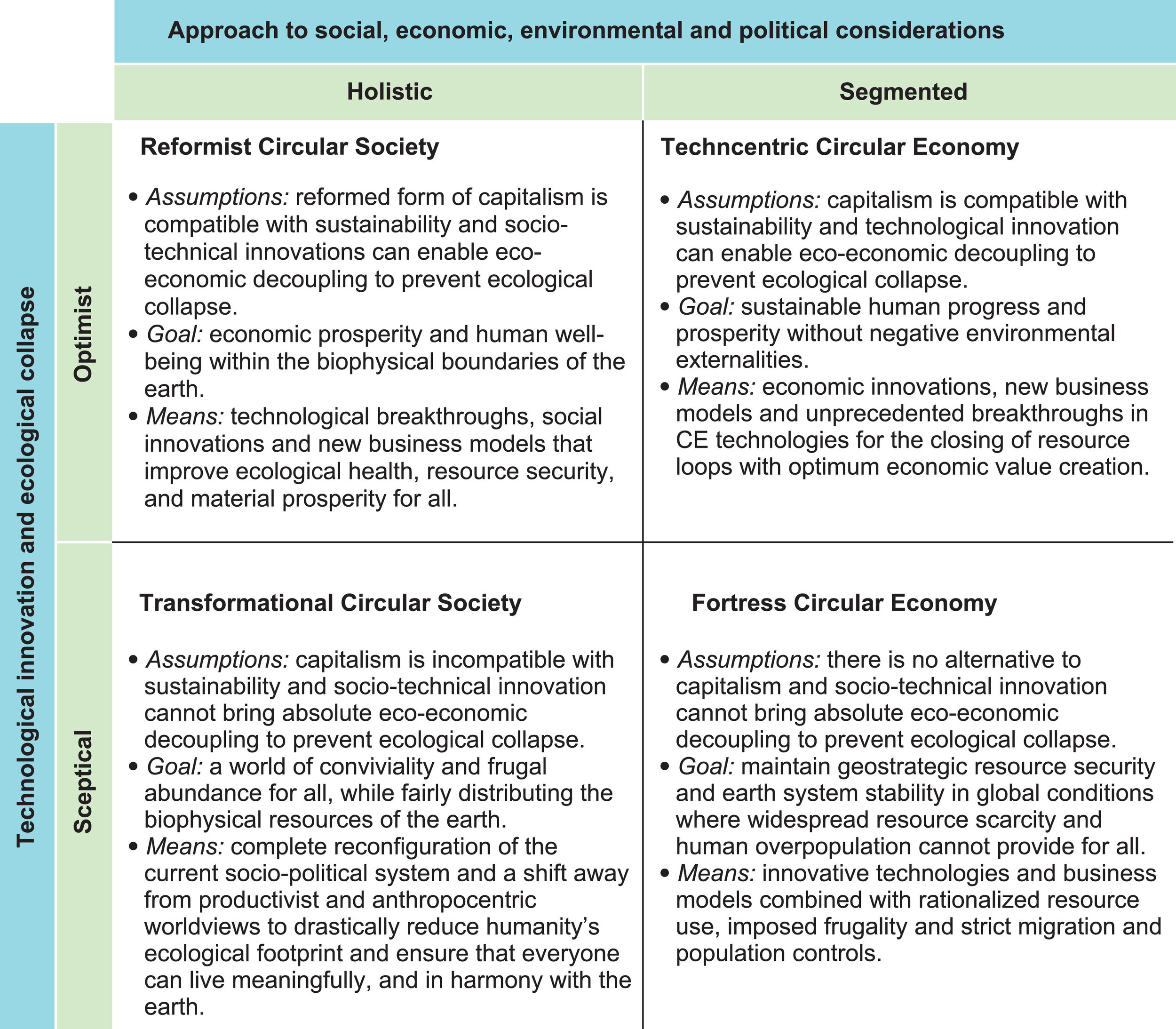

Calisto Friant et al. (2020) develop a typology of circularity thinking to clearly distinguish the diversity of circularity ideas through history, based on their approach to the above-mentioned challenges of socio-political inclusiveness and decoupling (see figure 1). The typology differentiates circularity discourses that are optimist or sceptical regarding the possibility of eco-economic decoupling and those that holistically integrate all the socio-political and ecological considerations of circularity or that have a segmented focus on resource-efficiency and economic prosperity alone.

Figure 1: Typology of Circularity Discourses

The hegemony of technocentric circular economy discourses

Recognising the diversity of circularity thinking and the manifold visions of a circular future can foster a cross pollinations of solutions and ideas to better address the major socio-ecological challenges that humanity faces. This pluralism is key for the CE concept to remain relevant in the 21st century especially in the face of the rising social inequality and unprecedented environmental collapse caused by the current socio-technical system. However, despite this rich diversity, most CE discourses in the public and private sectors fall in the technocentric circular economy discourse type, which doesn’t include social considerations and places unquestioned faith on technology (Calisto Friant et al., 2020).

“Recognising the diversity of circularity thinking and the manifold visions of a circular future can foster a cross pollination of solutions and ideas to better address the major socio-economic challenges that humanity faces”

Furthermore, in-depth research on CE policies at the EU level reveals that the EU has also taken a segmented and technocentric approach to the CE. While the EU has perhaps the most ambitious circularity agenda in the world to date, policy actions remain stuck in ‘end of pipe solutions’ - solutions that lack transformative socio-ecological components. Research by Calisto Friant et al. (2021) thus finds a lack of pluralism and diversity in the circularity approach taken by the EU, which simply assumes that economic growth can continue on a finite planet and doesn’t seek to sustainably address the systemic challenges of a circularity transition.

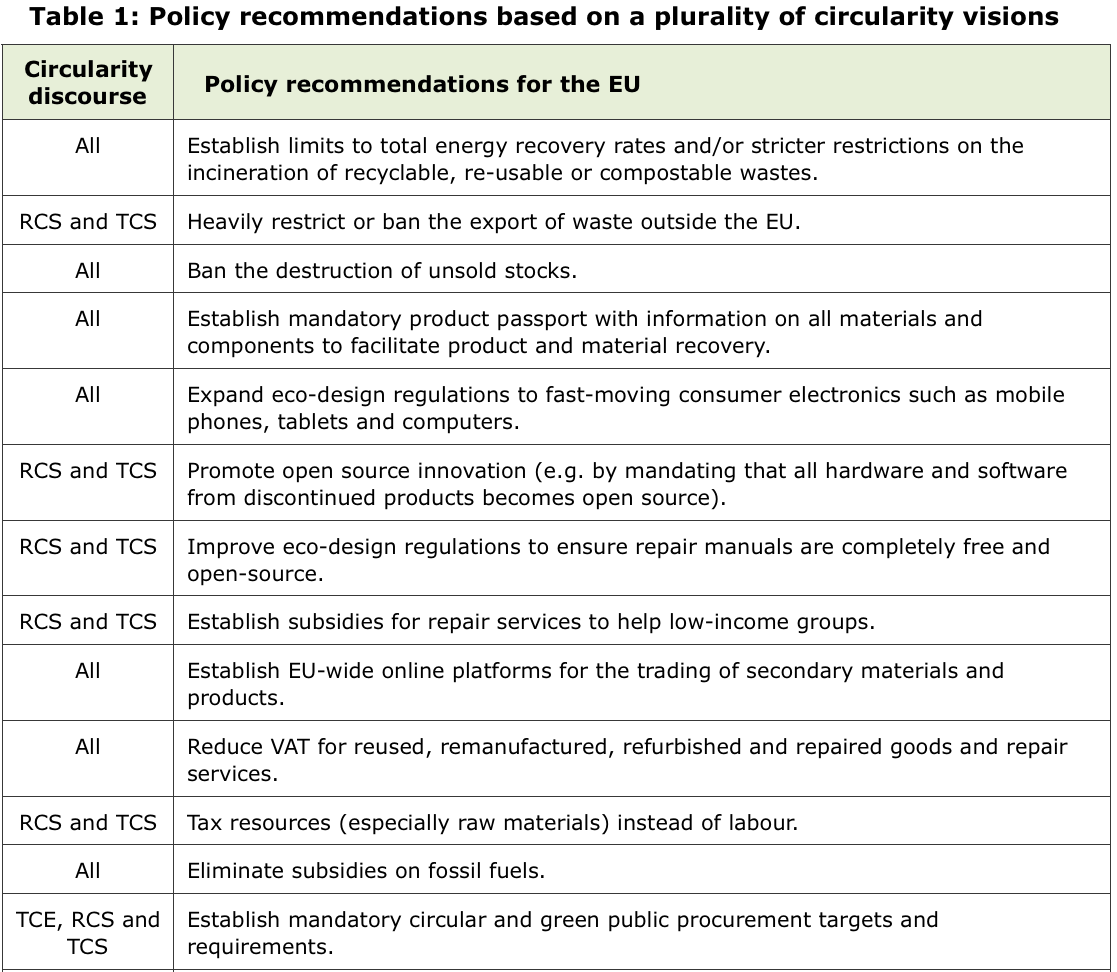

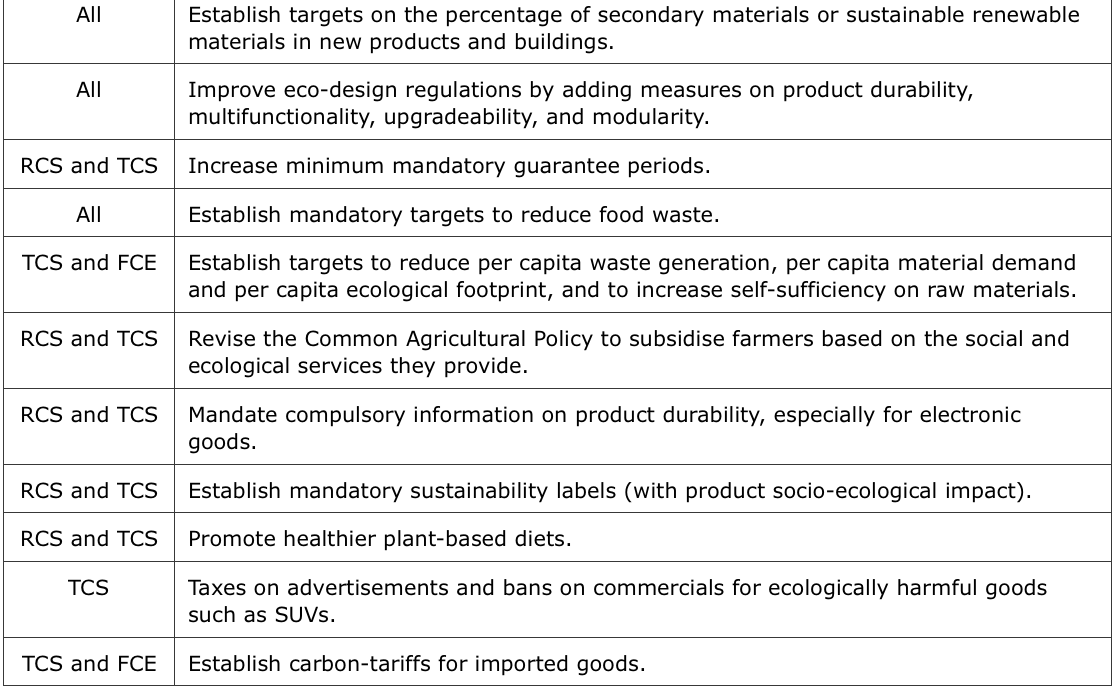

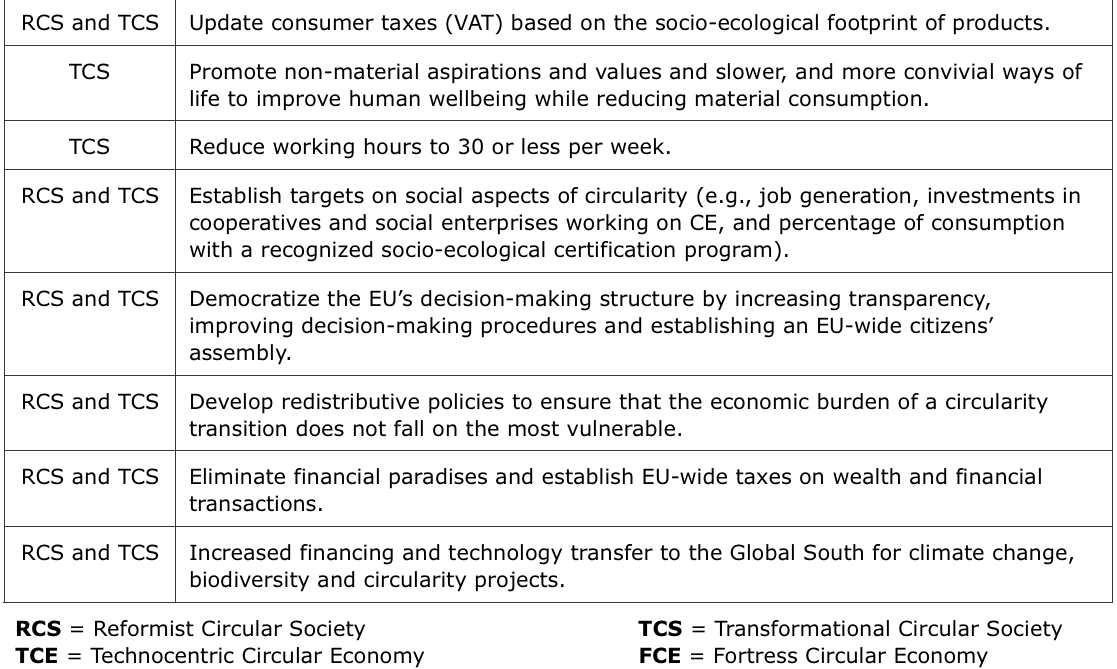

The above paper thus proposes 32 science-based policy recommendations to improve the EU’s circularity policies in a holistic and plural manner such as banning the destruction of unsold stocks, reducing VAT for recovered products and repair services, taxing raw materials instead of labour, increasing mandatory guarantee periods, reducing working hours to 30 per week, establishing taxes on wealth and financial transactions and creating an EU-wide citizens’ assembly that can take the lead on the socio-ecological transition (see table 1).

Concluding thoughts

All in all the CE is still very much an essentially contested concept (Korhonen et al., 2018), with many actors advancing their interpretations based on their political and economic interests. At this stage, the CE concept can go in many different directions and take a more or less transformative or reformist tone depending on how different actors interpret, communicate and implement it (Blomsma and Brennan, 2017).

“The CE concept can go in many different directions and take a more or less transformative or reformist tone depending on how different actors interpret, communicate and implement it”

Due to its inherent contradictions, and limitations, some scholars argue that the concept of CE should be rejected as a dangerous oxymoronic illusion (Bihouix, 2014; Giampietro and Funtowicz, 2020; Mayumi and Giampietro, 2019; Monsaingeon, 2017; Skene, 2018; Valenzuela and Böhm, 2017). Indeed, Giampietro and Funtowicz even argue that the CE is a “folk legend” that denies the uncomfortable truth regarding the impossibility of decoupling and the need to move to a post-growth and post-capitalist society (2020, p68). Giampietro and Funtowicz thus draw parallels between the CE and the Papal flat earth theory in medieval times; both forms of “socially constructed ignorance” to maintain the status quo and the authority of hegemonic elites (2020, p.70).

Others, like Genovese and Pansera, argue that the CE discourse can be “occupied” to re-politicize the concept and better address its systemic limitations (2020, p15). Rather than throwing out the baby with the bathwater, many scholars thus believe that the concept can be useful to envision and implement a fair and sustainable ecological transformation that effectively and equitably reduces humanity’s ecological footprint (Cullen, 2017; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Korhonen et al., 2018; Millar et al., 2019; Moreau et al., 2017; Schröder et al., 2020).

Whether we think we should completely reject the CE discourse or reclaim and improve it, one thing is certain, this new paradigm is here to stay. It might thus be necessary to act on both fronts and make sure that CE propositions are socially just and ecologically sound, while also promoting a plurality of alternative visions from the Global South and North alike such as Buen Vivir, Degrowth, Social Ecology and Radical Ecological Democracy (Kothari et al., 2019).

It is clear that moving away from purely technocentric CE discourses is necessary to deal with the key limitations of the concept. Embracing a plurality of circularity visions can open the imaginary regarding the manifold socio-political and systemic implications of a circularity transformation. This can ensure the CE concept is not used to justify new forms of growth-based accumulation and dispossession and can ensure that circularity policies actually lead to a reduction in the ecological footprint of human activities. This plurality is also key to ensure that circularity policies and actions lead to more just, democratic and convivial futures rather than to further inequalities and neo-colonialism.

By Martin Calisto Friant

December 2020

Martin Calisto Friant

Martin is a sustainability researcher and practitioner, currently working as a PhD researcher at the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University. Martin has an interdisciplinary academic background on international development studies, political ecology and urban planning from McGill University, the University of Melbourne, and University College London. He has over seven years of experience as a sustainability practitioner working on several projects in Africa, Europe, Oceania and the Americas. His current research focuses on circular economy, sustainability, degrowth, and deliberative democracy.

Bibliography

Albert, M.J., 2020. The Dangers of Decoupling: Earth System Crisis and the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution.’ Glob. Policy 11, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12791

Bihouix, P., 2014. L’âge des low tech : vers une civilisation techniquement soutenable. Seuil, Paris.

Blomsma, F., Brennan, G., 2017. The Emergence of Circular Economy: A New Framing Around Prolonging Resource Productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 21, 603–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12603

Bookchin, M., 1971. Post-scarcity anarchism. Black Rose Books, Montreal and Buffalo.

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W.J. V, Salomone, R., 2020. A Typology of Circular Economy Discourses : Navigating the Diverse Visions of Contested Paradigm. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104917

Calisto Friant, M., Vermeulen, W.J.V., Salomone, R., 2021. Analysing European Union circular economy policies: words versus actions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 27, 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.11.001

Campbell-Johnston, K., Calisto Friant, M., Thapa, K., Lakerveld, D., Vermeulen, W.J.V., 2020. How circular is your tyre: Experiences with extended producer responsibility from a circular economy perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 270, 122042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122042

Clube, R.K.M., Tennant, M., 2020. The Circular Economy and human needs satisfaction: Promising the radical, delivering the familiar. Ecol. Econ. 177, 106772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106772

Cullen, J.M., 2017. Circular Economy: Theoretical Benchmark or Perpetual Motion Machine? J. Ind. Ecol. 21, 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12599

Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N.M.P., Hultink, E.J., 2017. The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 143, 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048

Genovese, A., Pansera, M., 2020. The Circular Economy at a Crossroads: Technocratic Eco-Modernism or Convivial Technology for Social Revolution? Capital. Nature, Social. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2020.1763414

Giampietro, M., Funtowicz, S.O., 2020. From elite folk science to the policy legend of the circular economy. Environ. Sci. Policy 109, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.012

Gorz, A., 1980. Ecology as politics. South End Press, Boston.

Haas, W., Krausmann, F., Wiedenhofer, D., Lauk, C., Mayer, A., 2020. Spaceship earth’s odyssey to a circular economy - a century long perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 163, 105076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105076

Haberl, H., Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Brockway, P., Fishman, T., Hausknost, D., Krausmann, F., Leon-Gruchalski, B., Mayer, A., Pichler, M., Schaffartzik, A., Sousa, T., Streeck, J., Creutzig, F., 2020. A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environ. Res. Lett. 15. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab842a

Hickel, J., 2020a. The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecol. Econ. 167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.05.011

Hickel, J., 2020b. Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Penguin Random House.

Hickel, J., Kallis, G., 2019. Is Green Growth Possible? New Polit. Econ. 0, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

Hobson, K., Lynch, N., 2016. Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: Radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world. Futures 82, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.012

Klein, N., Ramos, T., Deutz, P., 2020. Circular Economy Practices and Strategies in Public Sector Organizations: An Integrative Review. Sustainability 12, 4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104181

Korhonen, J., Nuur, C., Feldmann, A., Birkie, S.E., 2018. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 175, 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.111

Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., Acosta, A., 2019. Pluriverse: a post-development dictionary. Tulika Books, New Delhi, India.

Latouche, S., 2009. Farewell to growth. Polity, Cambridge (UK).

Lekan, M., Rogers, H.A., 2020. Digitally enabled diverse economies: exploring socially inclusive access to the circular economy in the city. Urban Geogr. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1796097

Lindgreen, E.R., Salomone, R., Reyes, T., 2020. A critical review of academic approaches, methods and tools to assess circular economy at the micro level. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124973

Mayumi, K., Giampietro, M., 2019. Reconsidering “circular economy” in terms of irreversible evolution of economic activity and interplay between technosphere and biosphere. Rom. J. Econ. Forecast. 22, 196–206.

Millar, N., McLaughlin, E., Börger, T., 2019. The Circular Economy: Swings and Roundabouts? Ecol. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.12.012

Monsaingeon, B., 2017. Homo detritus-Critique de la société du déchet. Seuil, Paris.

Mont, O., Neuvonen, A., Lähteenoja, S., 2014. Sustainable lifestyles 2050: Stakeholder visions, emerging practices and future research. J. Clean. Prod. 63, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.09.007

Moreau, V., Sahakian, M., van Griethuysen, P., Vuille, F., 2017. Coming Full Circle: Why Social and Institutional Dimensions Matter for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 21, 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12598

Murray, A., Skene, K., Haynes, K., 2017. The Circular Economy: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Concept and Application in a Global Context. J. Bus. Ethics 140, 369–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2

Parrique, T., Barth, J., Briens, F., Kerschner, C., Kraus-Polk, A., Kuokkanen, A., Spangenberg, J.., 2019. Decoupling debunked: Evidence and arguments against green growth as a sole strategy for sustainability. Brussels.

Rijnhout, L., Stoczkiewicz, M., Bolger, M., 2018. Necessities for a Resource Efficient Europe, in: Lehmann, H. (Ed.), Factor X Challenges, Implementation Strategies and Examples for a Sustainable Use of Natural Resources. Springer, Cham, pp. 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50079-9_2

Schröder, P., Lemille, A., Desmond, P., 2020. Making the circular economy work for human development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104686

Skene, K.R., 2018. Circles, spirals, pyramids and cubes: Why the circular economy cannot work. Sustain. Sci. 13, 479–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0443-3

Valenzuela, F., Böhm, S., 2017. Against wasted politics: A critique of the circular economy. Ephemer. theory Polit. Organ. 17, 23–60.

Ward, J.D., Sutton, P.C., Werner, A.D., Costanza, R., Mohr, S.H., Simmons, C.T., 2016. Is decoupling GDP growth from environmental impact possible? PLoS One 11, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164733